Last week, a coworker asked me about my Enneagram type. I was skeptical when I read about its origins — the teachings of a spiritual teacher? My mind immediately jumped to Christian Science.

But after flipping through the first couple of pages of the Yes/Partly/No questions, I was hooked (warning: the test is a tad long):

“I want to win the approval of those in authority, sometimes even when I don't really like them.”

“I am uncomfortable when people want an emotional response from me.”

“For better or worse, I compare myself to others to assess how I'm doing.”

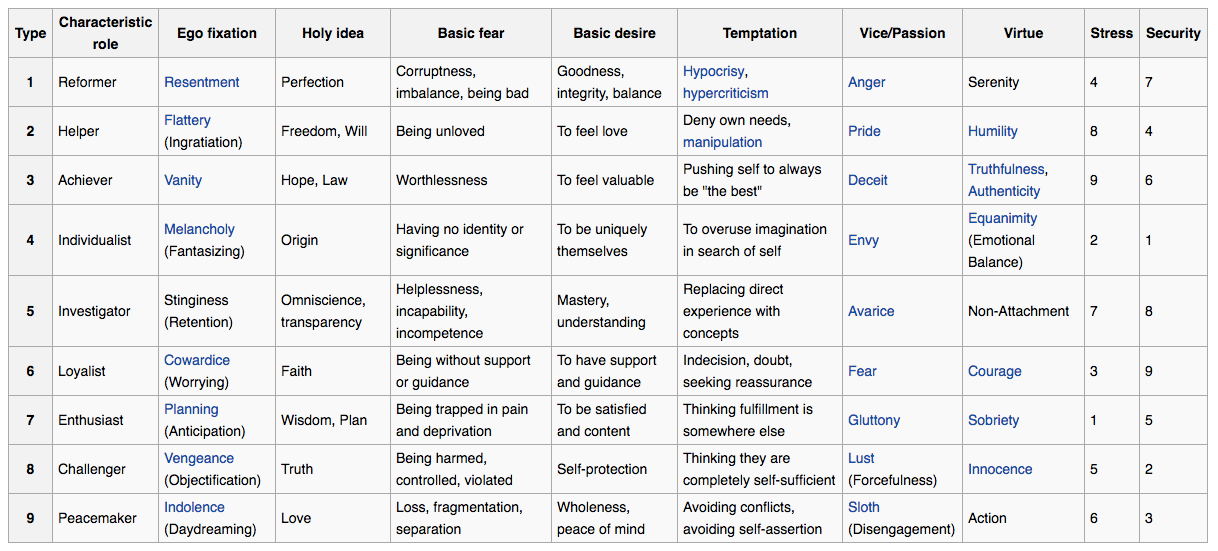

The framework is built on two foundational elements: a person’s basic fear and basic desire. My assessment was eerily accurate — but the skeptic in me wondered if all the fears and desires listed are simply universal human truths, and the test is more of a self-fulfilling prophecy.

A few scenarios come to mind that feel nearly universal with similar elements of fear or desire, but also carry a lot of variety in people’s choices (neglecting the inevitable outliers):

Recruitment: No one I know enjoys being an interviewee to recruit for a new job. The fear of riding the rollercoaster of possible emotions, from extreme joy and confidence to uncontrollable self-doubt, anger, and regret, makes the seasoned professional dread the process. Some people, however, love being an interviewer while others detest it and see it as a waste of time.

Winning the lottery: Most people would theoretically want to win a big jackpot (ignoring the slim odds and any negative consequences). But if they win, some would choose to immediately share the news with family and friends, while others would keep it secret, fearing the fallout.

Being ghosted: Most people hate being ghosted — yet some of those same people will still choose to ghost others, even though they despise the act.

These examples led me to a theory: people tend to fantasize about “best-case scenarios” in similar ways. Athletes visualize conquering their challenges. Students picture themselves in dream jobs. Marcus and I imagine the day we’ll stop having to plan or cook our own meals. The differences emerge when it comes to action — and those actions are shaped by a web of fears, desires, and circumstances.

I turned out to be an Enneagram Type 3 — The Achiever. On paper, it made sense: ambitious, driven by success, but sometimes overly concerned with external validation. The description felt uncomfortably accurate — especially the part about finding worth through accomplishments. One line in particular stopped me: “You may mistake your achievements for your identity.” It was like being caught in the act.

I make a lot of my decisions out of fear. I had to learn to say no to people because of my fear of missing out as a teenager. I still procrastinate sometimes because I fear not doing something perfectly. As an adult, there are also things I feel I should do — stay healthy and fit, perform well at my job, get married, have children. With bigger decisions like these, I try to give myself the space to ask whether I actually want to do them. But most of my energy for “figuring out what I want” gets spent on these big things, while the smaller, day-to-day desires often get overlooked.

Living in a city of constant competition, surrounded by fellow Type 3 achievers who recognize the rat race but can’t seem to quit it, I’ve started to wonder: if I didn’t have fitness, work, or money, what would make me who I am? What makes my soul happy beyond the checkboxes of life? I’m in search of these answers.

The Enneagram has pushed me to look deeper at my motivations — to ask whether I’m making choices because I genuinely want to, or because of realistic societal pressure, unvetted fear, or pure fantasy. It’s made me more honest with myself. Or sometimes, I pretend to dig deeper and blame my fear or desire as reasons for when, in truth, I simply just don’t want to do something.

Take your Enneagram test. Use it as a chance for an honest conversation about what scares you, what you secretly desire but won’t admit, what you think you should desire but don’t, and what actually brings you peace at the end of the day.

You might not make radically different choices after learning your type, but the conscious awareness can help you feel more in control in the constant shifting of circumstances, places, people, and timelines in this thing we call life.

My skepticism on the test hasn’t completely vanished, but I can’t deny this: the test gave me language for patterns I’ve always felt but never fully named. And maybe that’s the real value — not in predicting who we are, but in helping us ask better questions about who we want to be.

Until next time,

Bella